Note: This article was first published on the blog of the Guerrilla Foundation.

INSERT-GENERIC-BUT-GOOD-SOUNDING-SOCIETAL-OBJECTIVE-HERE

Vision. Mission. Strategy. Five-year plan. Ten-year plan. Theory of change. All terms that outline a way to achieve one or more goals under conditions of uncertainty. There are currently thousands of philanthropic foundations around the world. Thousands of visions, thousands of missions, thousands of strategies, thousands of plans. After a while, most of these blur into one another and regress toward a mean of envisioning a world free of poverty, war, disease and further environmental degradation. All that may sound rather appealing, but after overexposure to the same terms, overuse of buzzwords, and when constant pursuit of goals that are seemingly not getting achieved one needs to do some strategic reevaluation. There are more Foundations in the world now, than ever in the past, and even though we take pride in reduction of global poverty, for the first time this century world hunger is rising, and the environmental harm our species is inflicting on the planet has undeniably reached unprecedented levels – meaning there is a very, very long way to go.

Marshall Ganz said that “strategy is turning the resources you have into the power you need, to win the change you want”. Therefore, the first conversation we had at the Guerrilla Foundation, before we even had a name or tax number, was whether there is a need for us to exist and if so, what was it that we would do that others were not doing, and why this was worthwhile.

EXISTENTIAL ANGST

Philanthropic institutions are formed for many reasons, some are born out of family tragedies with emerging Foundations fighting to develop cures to currently incurable diseases, others are born of funders’ passions or unrealised dreams – many theatres, university libraries and concert halls have been erected by private money in such a way, then again such infrastructure has also materialized through much more superficial and narcissistic motives, as vanity has always featured prominently in philanthropic history. However, what does a grant-maker, philanthropic institution or Foundation make? With the rare exception of some community foundations and participatory funding platforms, Foundations generally have their endowments, which come from vast private wealth. In other words, the neoliberal system that champions ‘free’-market capitalism and allows exorbitant fortunes to be amassed by one or few individuals is the same system that allows for Foundations to exist. Moreover, most Foundations invest the funds of their endowments in various ways, corporate or government bonds or equities, and then give out the annual profits in grants. This means that the majority of funds of foundations are actually going into for-profit generating activities with a tiny percentage going to ‘public good’, and sometimes, much more often than Foundation COOs would like to admit, these investments go directly counter to what the grant-making is subsequently trying to cure or alleviate or improve. Peter Buffet from the NoVo foundation captures it best, “as more lives and communities are destroyed by the system that creates vast amounts of wealth for the few, the more heroic it sounds to “give back.” It’s what I would call “conscience laundering” — feeling better about accumulating more than any one person could possibly need to live on by sprinkling a little around as an act of charity. But this just keeps the existing structure of inequality in place. The rich sleep better at night, while others get just enough to keep the pot from boiling over.”

Identifying that the Charitable-Industrial Complex is a deeply entrenched, pernicious and deceptive element within the philanthropic sector, our first realisation was, that if we were to embark on starting a Foundation, one of its core aspects would be to shake up the foundation world. This was also the baptismal inception, when ‘Guerrilla’, a member of a small independent group taking part in irregular fighting, typically against larger regular forces seemed perfectly pertinent. An early intention was disrupting (another recently overused fad word but humour us), the philanthropic status quo, while also, staying small, staying nimble & decentralised and finally, using smart, often-unexpected techniques to bring about the desired change. Which then brought us to the final two ‘should-we-exist’ questions, what was the change we desired to see and what would be our techniques to get there.

RESISTING PHILANTHROPIC COLONIALISM & PURSUING THE GREAT TRANSITION

Despite the fact that so many mission statements are essentially an exercise in alternating synonyms, every foundation (and NGO, nonprofit, state agency, social business, CSR department) expends much time and effort crafting their personalized strategy document, usually for three main reasons: 1) the strategic focus is of personal importance to the founder or trustees, 2) this focus becomes the key, defining ‘brand identity’ of the organization and 3) the strategy acts as a roadmap towards assessing success in achievement of set objectives. However, many of these strategy crafters seem to think that they know best what’s best for the world and thus impose their limited worldview onto others. Enter philanthropic colonialism.

This is something we deeply wanted to avoid. So we sought counsel from people who dedicated their lives exclusively to an interplay of predicting and imagining viable & likely scenarios that the future holds: the Global Scenario Group (an international, interdisciplinary body convened in 1995 by the Tellus Institute & the Stockholm Environment Institute).

The GSG formally summarized their approach in the essay: Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead which emphasizes one crucial element, that history has entered a qualitatively new era of high global interdependence, termed the planetary phase of civilization (Fig 1 & 2). This echoes Michael Caine’s proclamation in Interstellar that “we must reach far beyond our own lifespans. We must think not as individuals but as a species.” Following from this premise, the GSG envision that three main classes of scenarios will emerge – Conventional Worlds, Barbarization, and Great Transitions.

Fig. 1 Characteristics of Historical Eras

Fig. 2 Graph depicting the emergence of the Planetary Transition

The Conventional Worlds scenario forecasts a future that unfolds without major surprising changes and essentially continues with current trends, driving forces, and prevailing values. One subscenario, Market Forces relies heavily on free markets that generate sufficient and timely technological evolution to address emerging environmental and social challenges while the Policy Reform subscenario assumes instead that governments mobilize to develop a coordinated, sustained, and effective set of policy adjustments to mitigate environmental disasters and social destabilization. On the other hand, Barbarization scenarios depict futures in which the market and policy adjustments of Conventional Worlds are inadequate to address such problems as climate change and social polarization, leading to devolution of social norms. In the Fortress World subscenario, global elites respond to impending collapse by mounting an authoritarian intervention to stop environmental degradation and social conflict. The elites retreat to protected enclaves, where they manage remaining natural resources and protect their interests, something akin to the movie Elysium. Outside these enclaves, the remainder of civilization endures poverty and degradation. The Breakdown subscenario ensues if the elites are unable to form a coherent, adequate response to the mounting crisis and the world descends into conflict and degradation, as institutions collapse. Finally, The Great Transition scenarios go beyond the market and policy adjustments of Conventional Worlds to envision a paradigm shift in institutions and values. The unrestricted growth directive of Conventional Worlds economies give way to steady state economies, the tendency toward inequality is countered by egalitarian social policies, and human values turn toward solidarity, well-being, and ecology, rather than individualism, consumerism, and domination of nature. The potential of a Great Transition is linked to the emergence of a global citizens movement to advocate for new values to underpin global society. In addition, the Eco-communalism, variant is characterized by extreme localism, while the New Sustainability Paradigm variant welcomes cosmopolitanism and global governance in a plural world. In all versions, civilization has a far smaller ecological footprint, societies are more equitable, and citizens have more leisure time to pursue fulfilling activities.

Fig 3. Scenario Structure with Illustrative Patterns

Fig. 4 Summary of Scenario Worldviews

Of course the Great Transition scenario is the one we feel most drawn to, the one most worth fighting for. Achieving the requisite paradigm shift and set of requisite value changes, behavioural patterns and wider social norms & socioeconomic systems is something the Great Transition goes into at length with varying push and pull factors, risks and likely trajectories. The Smart CSOs Lab, an international network of more than 1,000 activists, civil society leaders, researchers and funders (and now a Guerrilla Foundation grantee), encapsulates this shift well (Fig 5). The three levels, culture, regimes and niches capture the main interconnected strata, where moving from left to right we see seeds of the new economy slowly sprouting to usurp the old, unsustainable economic systems which are also steadily collapsing, thus shifting the old consumerist, growth culture to a global, eco-social culture that then further enforces a healthier new economic system that allows participatory and democratic structures like The Commons to thrive. This is the rough outline of a plan that we can get behind and work towards both as a group of individuals and as an organisation.

Fig. 5 The Smart CSOs Model

SYSTEMIC ACTIVISM

This left us with the how to get there, our technique to achieving the desired goal. Transition. ‘The act of passing from one state to the next’. Metamorphosis. Alteration. Transmutation. These are all synonyms of the dynamic process of Transitioning, and while the multiplicity of potential outcomes is on the one hand refreshing, because it tempers the hubris of forecasting omniscience, and on the other frightening, because it also does not provide a clear recipe to be followed thereby allowing for a larger margin for failure. However, it does employ the BuckminsterFullerian approach of not changing things by fighting against the existing reality, instead, changing the system by building a new model that makes the old model obsolete.

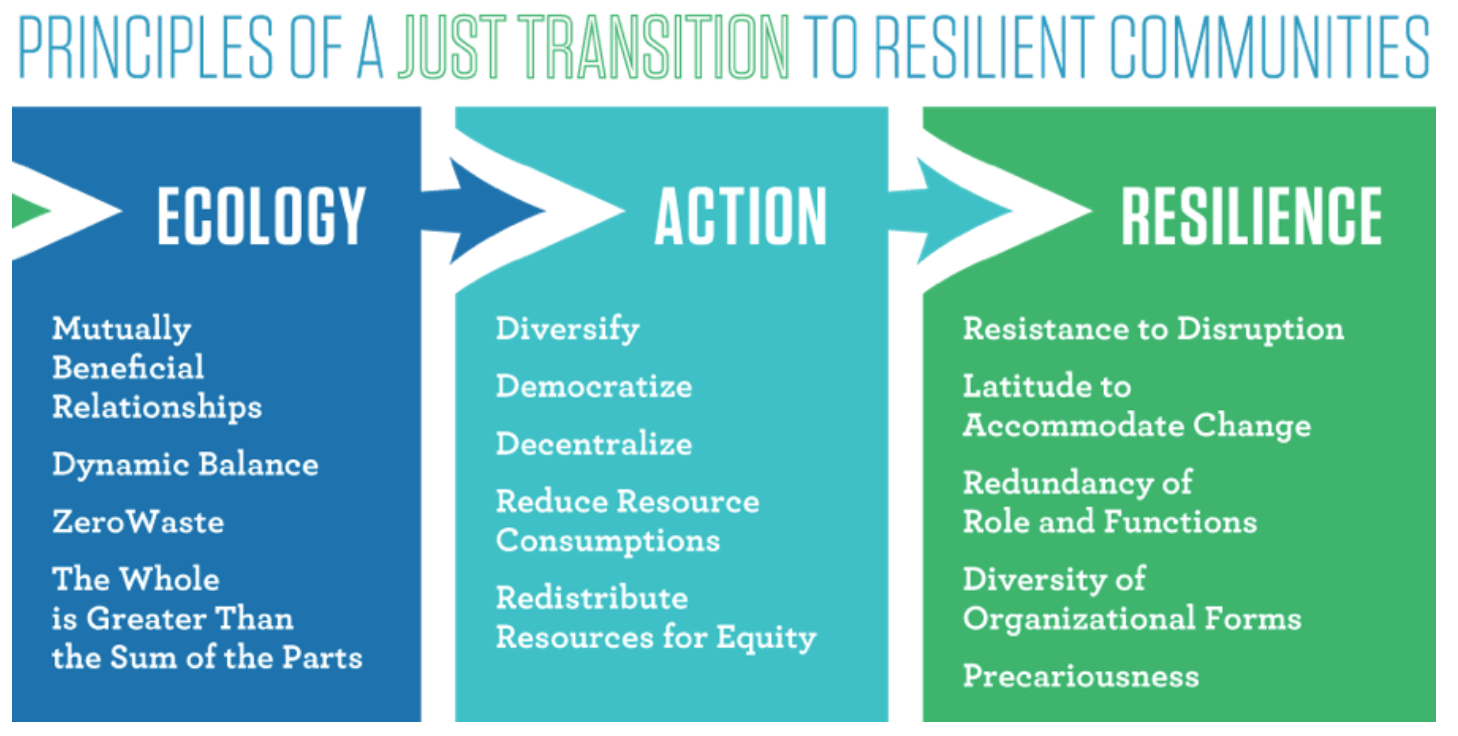

First used in 1998, by Brian Kohler, a Canadian union activist, a sister model with a similar name, the Just Transition, is a framework that has been developed by the trade union movement to encompass a range of social interventions needed to secure workers’ jobs and livelihoods when economies are shifting to sustainable production, including avoiding climate change, protecting biodiversity, among other challenges. The use of this concept has broadened over the years and quite a few organisations (environmental & climate justice, foundations) use the concept of Just Transition, sometimes quite close to the union approach, as in Friends of the Earth & Greenpeace, and sometimes expanding from the labour component of it to a more holistic view such as Edge Funders Alliance (also an oragnisation we support and are network members of). It comes in very handy for doers like us, because it offers very concrete steps and some not-so-concrete steps, but key blueprints, which we can then work with to move towards our Transition whether it be Great or Just or both.

Fig. 6 The Just Transition Framework

The Just Transition framework reiterates the Great Transition model with an emphasis on power shifts and movement from an extractive economy to a living economy. An extractive economy is the current status quo, where labour is exploitative and far from the social utopia predicted by John Maynard Keynes in 1930, that we would have achieved a 15-hour working week through technological advancement. Moreover, finite resources are extracted, such as fossil fuels, or ecosystems are pressed for maximization of profit margins such as in monoculture farming, leading to environmental degradation. Nations still depend on their armies for geopolitical governance and military spending is exorbitant. Wealth and power remain enclosed in the hands of the few, and the system actually favours bottlenecking of this power divide so that the wealthy become exponentially wealthier. On the other hand a living economy focuses on cooperation in labour, and on democratization, decentralization, localization of power in a bottom up fashion. Natural resources are used in a regenerative framework, and examples of this abound, from water retention mechanisms to permaculture agronomy hallmarks of today’s ecovillages. Ecological and social wellbeing are the main priorities, which then guide much more diplomatic, and humanistic geopolitical governance strategies. Getting to such a living economy will certainly require transitionary phases, however with a shift in intentions and goals we switch from the extractive to the regenerative mindset, which then allows for more specific techniques to facilitate these shifts (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 movementgeneration.org

One overarching element to the Great & Just Transition, is that they both demand systems thinking when it comes to bringing about change. According to systems theory, a system is an entity with interrelated and interdependent parts however it is more than just the sum of its parts. Which is why if you want to change the system but constantly just focus on the part independently, you are very unlikely to be able to change it, by virtue of this quality.

Activism, perhaps best refined by Wikipedian crowd wisdom, ‘consists of efforts to promote, impede, or direct social, political, economic, or environmental reform or stasis with the desire to make improvements in society.’ This working definition acknowledges the three main directions of promoting, impeding or directing change, as well as the four main boundaries social, political, economic and environmental, and combined with the mission of societal improvement (where we now have our Just Great Transition placeholder). In Foundation jargon, activism would traditionally fall under social justice, because activism as a term is something foundations traditionally (and still to a great extent) have shied away from. Regardless, in the U.S. only 15% of philanthropic giving goes to social justice causes and if we remove direct service provision from the equation the remainder becomes infinitesimal. For Europe, these stats are not available, but philanthropic institutions are generally more conservative and traditional in their approach to grant-making meaning the activism space is starved for support. With the exception of EdgeFund UK, Bertha Foundation, XminusY Foundation, Solidaire, Urgent Action Fund and a couple of others, there are simply very few players that prioritise activism institutionally as an integral part of their strategies. Therefore we felt the threshold of our existential angst sufficiently lowered for Guerrilla Foundation to come into existence, with an exclusive focus on activism as the vehicle for change, which would follow the path of the Just Great Transition, that would invariably work at dismantling the industrial-charitable complex along with the rest of the old paradigm – to create a world where there is no need for Foundations to exist in the first place. In addition, we wanted to combine the systems thinking approach with activism, to strengthen the big-picture thinking and always try to bring the focus on root causes behind societal problems, for not much has changed since the time that Henry David Thoreau wrote that ‘there are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.’

Fig. 8 Symptoms versus Root Causes

Therefore Systemic or Systems Change Activism is what we’re banking on as a powerful and overlooked means for bringing about social change. At a time when grassroots social movements are starting to grow, embodied most recently by Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements, that transcended borders and race and age, and are a power for change to be reckoned with.

However, activists can take many shapes and forms and are the bedrock of community-level change. They can be students, ecoactivists, reproductive rights protesters, equal pay campaigners, shareholder activists, political leaders & legislators, gender rights advocates, civil disobedience artists etc. However, the exact impact of movements is frequently too elusive to capture. That is often a limitation of advocacy work, that it eludes quantification, and is difficult to pin down, nevertheless, while sharpening the qualitative methods in depicting this impact, it is necessary to sustain philanthropic support to projects that have societal peace, justice and wellbeing at their core, even if the ROI is not attainable per se.

Fig. 9 Systemic Activists at work within the Smart CSOs Model

Four years ago at TEDxWhitechapel, the theme for the conference was ‘Visions for Transition: challenging existing paradigms and redefining values (for a more beautiful world)’, TED organisers really tapped into the zeitgeist and they articulated quite aptly what we are trying to accomplish, just via the Foundation angle. Challenge existing paradigms and redefine values for a more beautiful world by enabling and supporting audacious, systems shifting activism.

Let’s see how we fare.